What a widely attacked experiment got right on the harmful effects of prisons

Published: October 3, 2018

The Stanford Prison Experiment is one of the few scientific studies to enter the public consciousness through , , , and .

Recently, it has been making headlines in a very bad way.

In 1971, Stanford University psychology professor Philip Zimbardo . He randomly assigned normal, healthy, emotionally stable male college students (without criminal records) to be ŌĆ£prisonersŌĆØ or ŌĆ£guardsŌĆØ in a fake prison.

Within six days, Zimbardo ended the experiment. The ŌĆ£guardsŌĆØ were torturing the ŌĆ£prisoners,ŌĆØ and the ŌĆ£prisonersŌĆØ were rebelling or experiencing psychological breakdown.

In news articles, the Stanford experiment has been and ŌĆ£.ŌĆØ It has been for experimenter interference, faked behaviour from participants and for research design problems, among other things.

These serious critiques have generated in academic circles and in news articles about what, if anything, we can learn from the experiment.

And yet, as someone who studies prisons, IŌĆÖm struck by how much the Stanford Prison Experiment got right. A wealth of other research suggests prisons have serious detrimental effects on prisoners and prison workers alike.

What the research says

Living and working in prison is .

Some people are better at repelling these effects than others. Even so, and suffer from high rates of and other devastating conditions. For many prisoners, these conditions continue after prison and can be .

We have long known that prisons are damaging places for both prisoners and prison workers. In his 1956 book, , Princeton sociology professor Gresham Sykes explained that incarceration deeply injured prisonersŌĆÖ dignity and self-concept. He also described how prison officers became ŌĆ£corruptedŌĆØ by the prison environment with its contradictory imperatives, impossible-to-enforce rules and necessary compromises.

In the 60 years since SykesŌĆÖs book, research in diverse prison settings and many of his findings.

The role of prison design

These insights extend beyond contemporary prisons in the United States. Prisons in , and , known for their humaneness, also cause harm.

Indeed, , but not destroy, the prisonŌĆÖs negative impacts. But , in many Western countries, the main goal when designing prisons has been containment and security, not prisonersŌĆÖ physical and mental health.

Popping up in the U.S. in the 1980s and 1990s, supermaximum security prisons (Supermaxes), which contain prisoners in solitary confinement in small concrete cells for , are a design.

Prisoners to these Supermax prison regimes. Some are able to withstand the conditions, others break down within hours of their arrival. We do not yet fully understand why people react differently, but we do know that Supermax prisons have an array of including .

Not just prisoners

Prison staff are also affected. The history of American imprisonment is also filled with examples of people with good intentions becoming ŌĆ£corruptedŌĆØ by the prison.

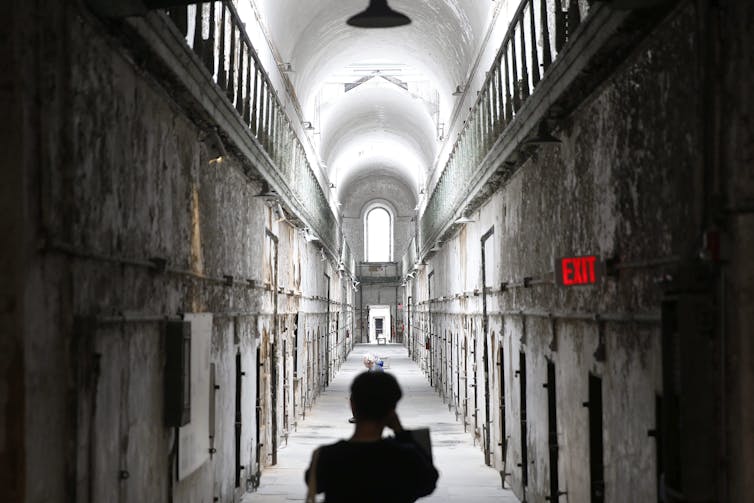

▒╩▒▓į▓į▓§▓Ō▒¶▒╣▓╣▓įŠ▒▓╣ŌĆÖs opened in 1829. Progressive Philadelphia penal reformers designed Eastern to be more humane than other prisons, with prisonersŌĆÖ physical and mental health in mind. They implemented a routine ŌĆō combining work, education, mentorship and outdoor exercise ŌĆō to benefit both prisoners and society. Finally, they sought to protect prisonersŌĆÖ identities so they could re-enter society without stigma.

Within five years of the prisonŌĆÖs opening, however, the penal reformers, now prison administrators, had betrayed their humanitarian goals.

They , out of necessity or convenience, so the prison functioned smoothly. In the process, they sacrificed the regimeŌĆÖs humanitarian and prisoner-focused elements.

EasternŌĆÖs administrators , including what we now call waterboarding, held misbehaving prisoners after their sentences had expired and justified these actions as beneficial to prisoners.

These gaps between theory and practice, including the use of torture punishments, were common at in the 19th century and into the 20th. engaged in similar malfeasance despite their apparently genuine commitment to humanitarian values.

The situation was even more dire at prisons that were explicitly and .

Beyond the Stanford experiment

Even including these past failures, modern prisons rarely devolve as quickly and decidedly into a den of overt torture and serious mental breakdown as seen in the ŌĆ£Stanford Prison.ŌĆØ

It does happen ŌĆō and the retaking of are graphic illustrations of how prison can unleash the worst of human nature with terrible consequences ŌĆō but such extreme cases remain rare. PrisonsŌĆÖ negative effects are typically less dramatic and do less to capture the public imagination.

There is something about prisons that is damaging. But what is it?

Even the most humanely designed prisons have negative effects on the people living and working inside. And that is the deep truth we are still seeking to understand and the Stanford Prison Experiment effectively illustrates.![]()

is an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Toronto Mississauga.

This article is republished from under a Creative Commons licence. Read the .